Trail of Tears

America’s treatment of its indigenous people was undeniably cruel and severe, culminating in the decades long practice of Indian removal, relocation, and ethnic cleansing. Between 1830 and 1850, approximately 60,000 Native Americans of the Five Civilized Tribes (Cherokee, Muscogee, Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw) were forcibly removed from their homelands in the Southeastern United States and relocated to a designated Indian Territory west of the Mississippi. Thousands died from exposure, disease and starvation either before, during or shortly after their grueling journey.

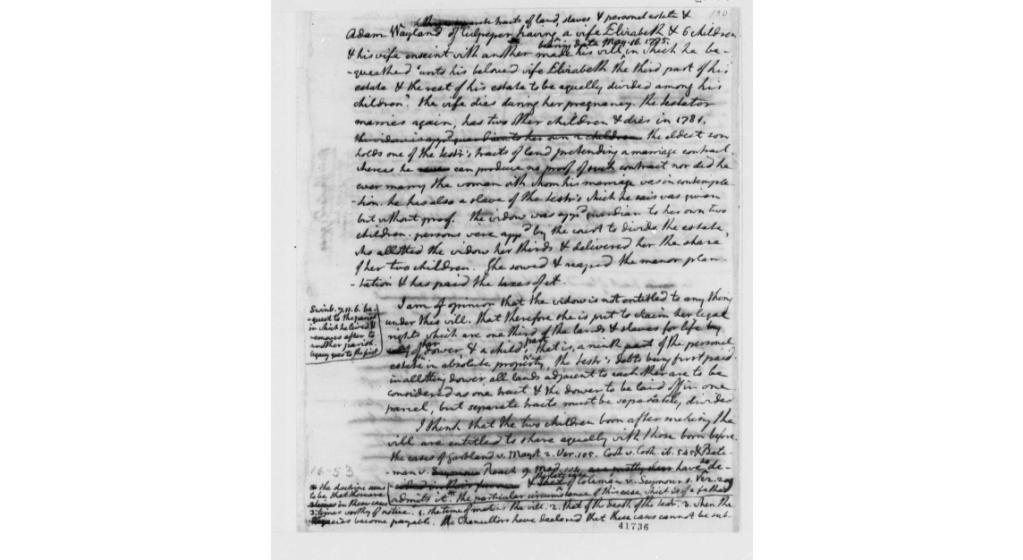

What some forget is that the experience caused a major rift within the ranks of the Indian population itself. There were a few who relocated voluntarily. They were known as the “Treaty Party,” as they obeyed the terms of the Echota Treaty which exchanged Cherokee tribal lands in the east for lands in the west. While the federal government viewed this treaty as valid, it was never formally accepted by recognized Cherokee leadership and the majority opposed its provisions. Those who did not relocate of their own volition began being forcibly removed in 1838 via an overland march that has become known as the “Trail of Tears.” The ones who survived that march, when they arrived in the western territory, clashed with the smaller “Treaty Party” who were already there, killing many of them.

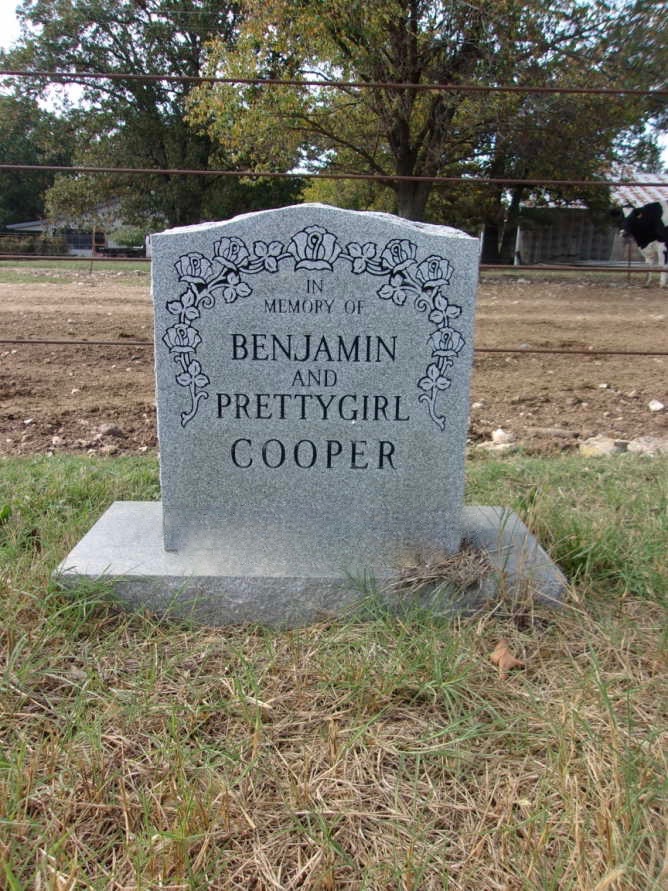

Benjamin Cooper ( my daughter-in-law’s 5th great grandfather) and his wife Oowoduageyutsa (Pretty Girl of the Cherokee nation) voluntarily left for the Indian Territory in Oklahoma in 1834. They both died there in 1852. His son, Cornelius Benjamin Cooper, and his family decided to avoid the possible violence awaiting them in Oklahoma and instead set their course for Rusk, Texas where they settled among other native families who made the same choice.

Michael Ondrasik and Home Video Studio specialize in the preservation of family memories through the digitalization of film, videotape, audio recordings, photos, negatives and slides. For more information, call 352-735-8550 or visit our website.